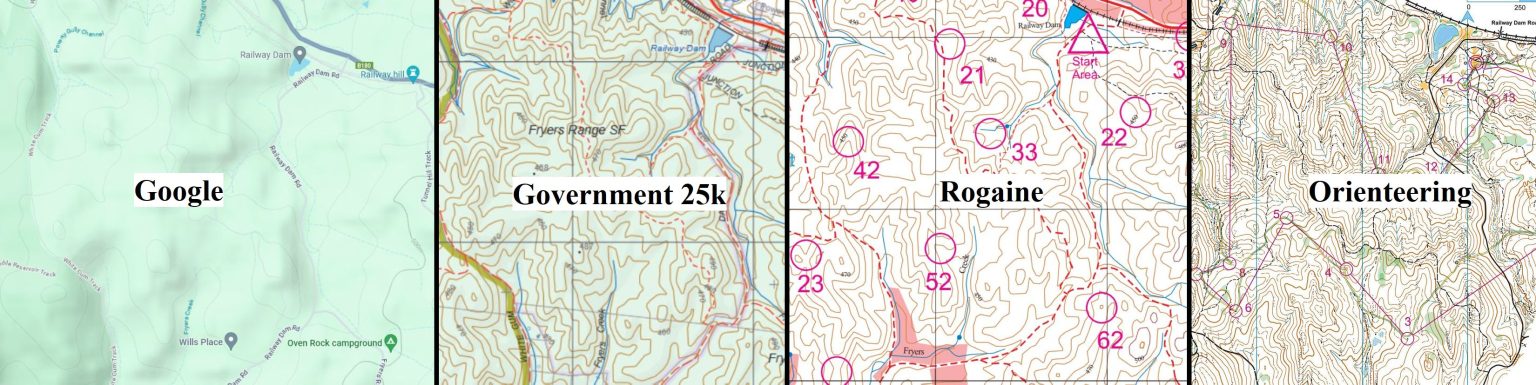

Orienteering maps differ from most other maps in providing greater detail and a high level of accuracy. Forest maps are mapped at 1:15,000 and Sprint maps at 1:4,000. This compares with the highest detail forest maps from other sources which are between 100,000 and 25,000 scale.

This difference is achieved by time spent field checking every feature on the map. This page explains in simple terms how an orienteering map is crafted. It covers five sections:

Orienteering started as a sport in Scandinavia over 100 years ago. Early events were based on whatever maps the organisers could get their hands upon, often government issue maps.

As the sport developed, orienteers started making their own maps. The first such map was produced in secret by Norwegian orienteers during the German occupation of their country in 1941.

For many years map makers in different countries followed different paths in the creation of maps. In 1969 the International Orienteering Federation released the first specification for orienteering maps to ensure all maps used the same symbology.

In the following decades the specification of orienteering map standards has evolved in response to changes in the sport and changes in mapping and printing technology. The history.

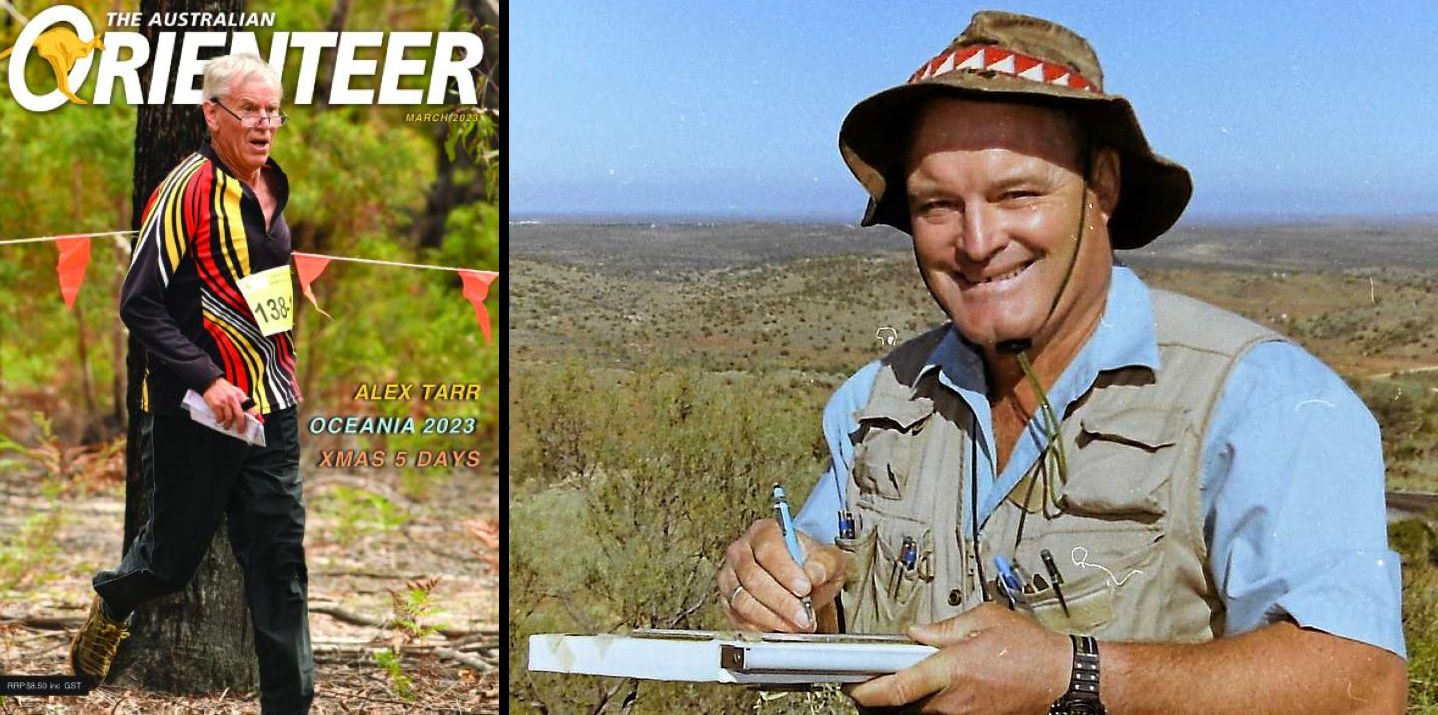

Australian orienteering mappers Steve Key and Alex Tarr have played a part in the evolution of the standard of orienteering mapping. Steve Key created the Kooyoora map used for the 1985 world Championships. This map is credited with extending the mapping specification to “extreme terrains”. The Eppalock maps produced by Alex Tarr helped define how rock outcrops would be mapped in the specification.

The current map specifications continue to evolve thanks to the work of the IOF Map Commission. Australian mappers have played their part in this work. Adrian Uppill is a recent past member of the commission and contributed to the colour definitions of the specification to reduce disadvantage experienced by colour blind competitors. Fredrik Johansson is the current Australian member of the Map Commission.

There are currently four map specifications for the production of orienteering maps

The first step in creating an orienteering map is to build a base map from available data sources. For many years this base map was created using analog photogrammetry derived from aerial photography. Many of Australia’s older orienteering maps are based on the work of photogrammetrist Chris Wilmott.

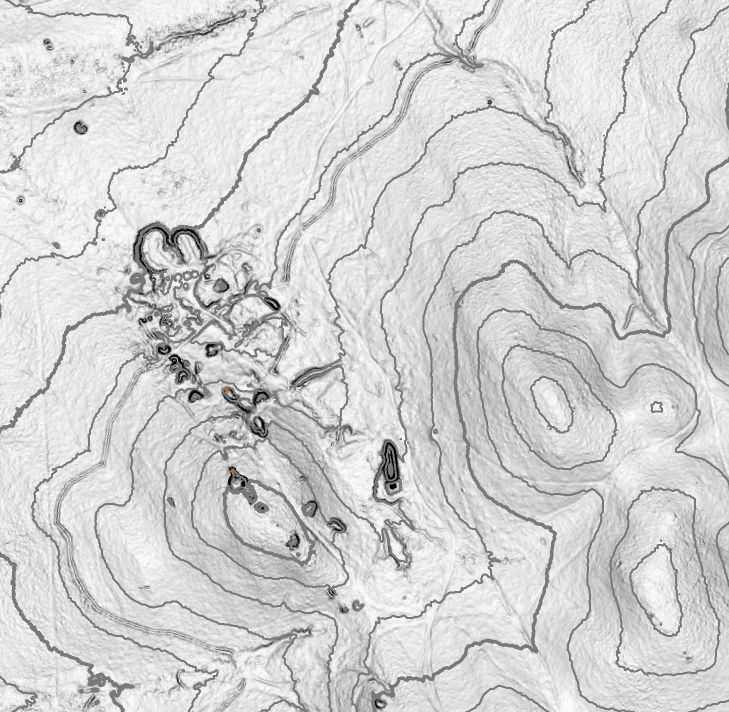

Today basemaps are generally derived from digital data. Lidar (laser imaging, detection and ranging) [link to paper on lidar] is the preferred data set, although this is not always available. Lidar data is processed using mapping software to produce very reliable contours, and helpful interpretation of vegetation.

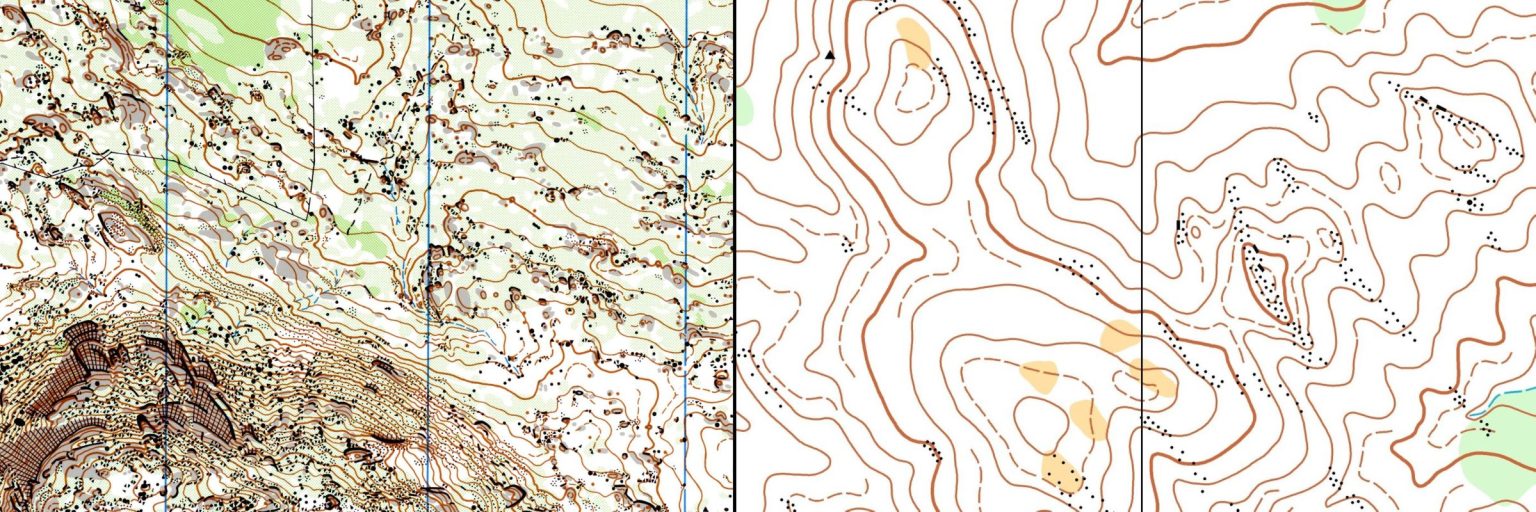

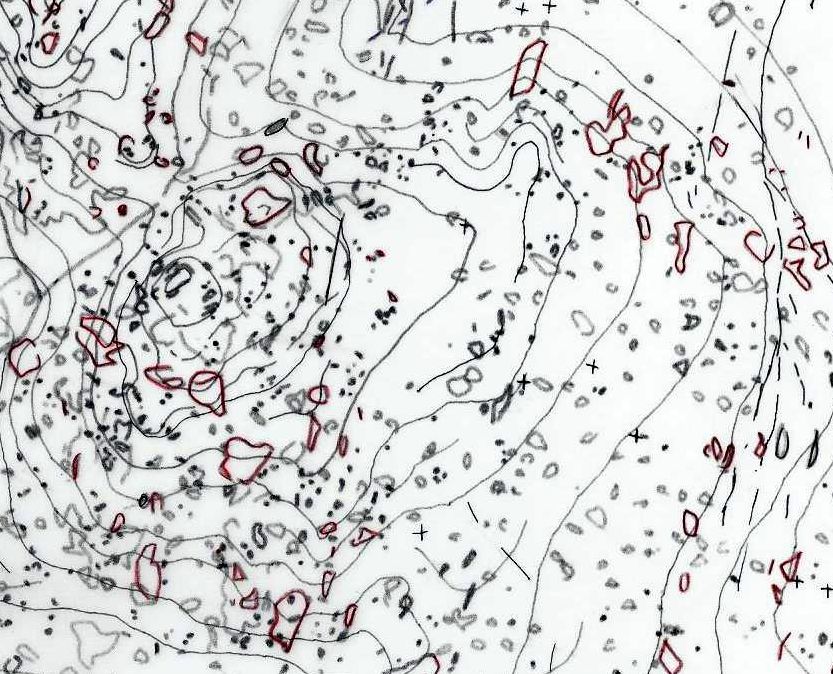

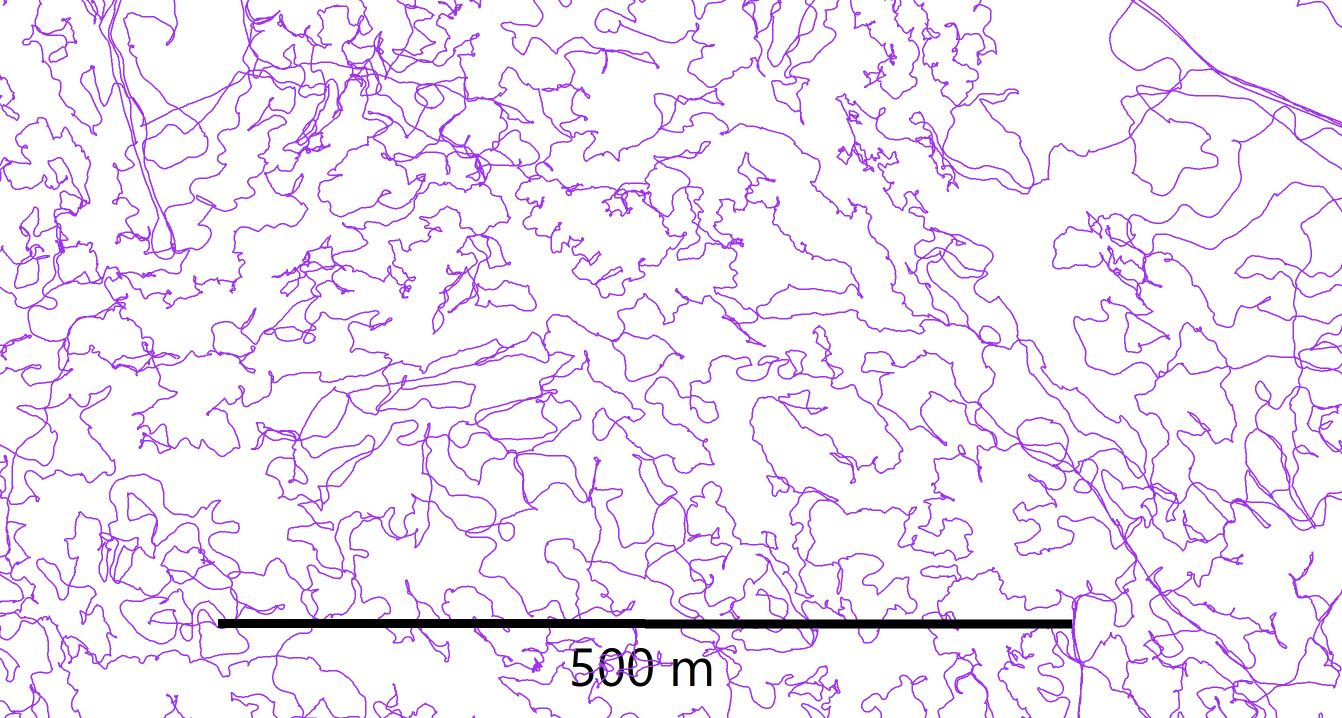

A mapper uses the base map to check every feature in the field and draw an orienteering map. In the days of analog photogrammetry the tools of the trade were a copy of the base map overlaid with drafting film. The mapper drew the field work version on the film using coloured mechanical pencils. The mapper would visit all the features indicated on the base map as well as explore the blank spaces, because the aerial photos did not reveal every feature.

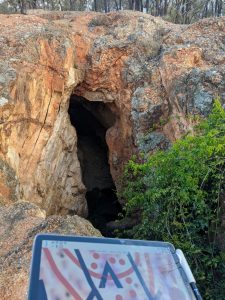

Many mappers today use digital tablet technology with inbuilt gps functionality as their mapping tool of trade. Some add a corrected gps functionality to improve gps accuracy to withing a metre. Digital tablet technology has many advantages-

A tablet in the Field

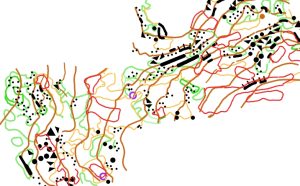

An example of field drafting – each orienteer does this differently

Field work is time consuming. A square kilometre of granite terrain may require the mapper to walk 100 kilometres over between 40 and 50 hours of mapping. An area of complex mining detail may be just as demanding, but most mining maps have significant areas of simpler spur gully terrain so the total effort for the map will be reduced. A spur gully map generally requires between 8 and 15 hours per square kilometre and walking approximately 20 to 30 kilometres. Times increase with a poor base map or complexity of vegetation. A complex granite map may take a month or two of full-time work to complete.

There is no single workflow used by all orienteers. However, most will redraw their map on a desktop computer using the fieldwork copy as a template. This allows neater drafting, and less time in the field.

Even if the mapper does most of their drafting in the field, there will still need to be compliance testing undertaken back in the office. The purpose of this testing is to make the map as compliant as possible with the international specification. Are some features too close together? Are some lines too short? Are some area symbols too small? The more complex the map, the more of these issues that will arise.

For a bush map drafting time will generally be between 20 and 25 per cent of the field work time. For a sprint map these times will be reversed. A sprint map requires much more attention to drawing detail than a bush map.

Orienteers need to understand that our sport is not large enough to support a cadre of professional mappers.

There are only a limited number of events per year with sufficient entries to fund the creation of a new map. As an example, and Easter carnival based on all new maps may require between 60 and 70 days of full time work (base map prep, field work, travel, drafting and compliance checking). A longer Australian Championships carnival may require between 100 and 120 days of full-time work to produce all new maps. If one mapper were to undertake all this mapping, there would be significant extra costs to cover accommodation. Mappers tend to specialise in one of the three main forms of mapping – bush, sprint or MTBO- spreading the available remuneration between mappers. Within bush mapping there is sometimes specialisation in one of the more complex terrain types. Further, where mapping is remunerated, it is often at the rate of the minimum wage. In total these events will not provide a basis for a career.

This helps explain why today most mapping is undertaken on a voluntary or semi-professional basis. Each state has a small number of mappers who service the needs of their state. Many of these mappers will have retired from the workforce and have developed their skills later in life. Older mappers may have a short mapping career. This means the sport needs a small but steady stream of new mappers. New mappers need the opportunity to learn by doing. Most experienced mappers will admit that their early efforts left something to be desired.

If, as an orienteer, you don’t like a map, be tolerant. Maybe the mapper was given a poor base map. Maybe they see the terrain differently to you. Part of the skill you need as an orienteer is the ability to adapt to different mapping styles. Unconstructive criticism, at its worst, will deplete the pool of active mappers.